![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/assets/_processed_/c/c/csm_Headerbild_Chiffriermaschinen_Rainer_26ae4b45eb.png)

[Translate to English:] Photo: CC BY SA 4.0 Konrad Rainer, Deutsches Museum Digital, Inv.-Nr 2013-1092

Digital cultures of technology and knowledge

Object (hi)stories of historical cipher devices

Early, elegant typewriters, mythical devices of World War II, 1970s espionage equipment and copy-proof welded black boxes: The cryptographic collection at the Deutsches Museum contains many rare und unknown objects. Our aim is to explore the backgrounds and origins of these devices, which will be on display in our new permanent exhibition Image Script Codes.

Content

- Digital cultures of technology and knowledge

Edited by

Dr. Carola Dahlke

CuratorComputer Science and Cryptology Department

Studies

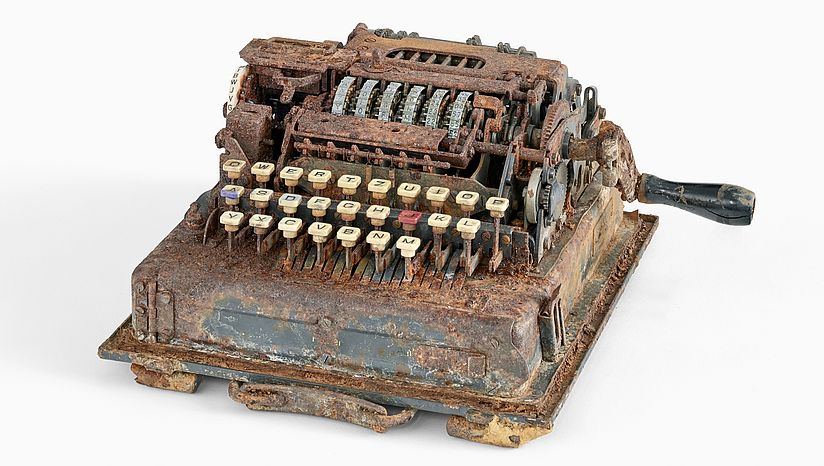

In 2017, amateur treasure hunters come across an unusual find in a forest close to Munich: this Schlüsselgerät 41 had presumably been buried at the end of the war. Photo: CC BY SA 4.0 Konrad Rainer, Deutsches Museum Digital, Inventar-Nr. 2017-803

The cipher device “Schlüsselgerät” SG-41 and its inventor Fritz Menzer (1908–2005)

The German cipher device Schlüsselgerät SG-41 is much rarer than its famous predecessor, the Enigma. The Deutsches Museum owns two destroyed artefacts. Both devices are the subject of several studies at the same time, as the historical background, the person of the inventor, the encryption algorithm and the objects themselves (conservation research) still raise many questions.

Link zum DM-Podcast Schlüsselgerät 41:

https://youtu.be/nwAGr8vNuAo

Link zum Video Restaurierungsforschung der Leibniz-Museen über das SG41: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nB2OI6xJv1E

Link zur Veranstaltung HistoCrypt2018/ Veröffentlichung über das SG-41:

https://ep.liu.se/ecp/149/020/ecp18149020.pdf

The research results of this study will be used to create an animated film in Menzer’s footsteps as part of the new permanent exhibition Image Script Codes. Photo: © Grafik: Cosimo Miorelli | Produktion: Libellulafilm Nina Mair & Robert Jahn

Tracking the inventor

The toolmaker and later cryptologist Fritz Menzer headed the encryption department of the Wehrmacht High Command. Numerous inventions were made by him, such as the cryptographically extremely secure cipher box and the SG-41 cipher device, but were too late in production for the war. Some interesting details about this largely unknown inventor could already be taken from TICOM documents, German archives and from personal interviews with relatives.

(TICOM = the Target Intelligence Committee (U.S.A. and U.K.), conducted interviews and investigations with prisoners of war immediately after the end of the war and recorded them in TICOM documents; since 2011, most of them have been released by the NSA as so-called ‟declassified documents”. )

In 2013, the Deutsches Museum acquired at auction a heavily restored Schlüsselgerät model Z that was salvaged from a lake in eastern Germany, with ten-figure traffic to be used for encrypting weather reports. Photo: Deutsches Museum, Konrad Rainer | Konrad Rainer

Tracking the algorithm

Although the basic operation of the Schlüsselgerät 41 is known, it has up until now not been possible to understand every detail and simulate the encryption algorithm due to a lack of design drawings or intact devices. For this reason, as part of the 3D Cipher study of the Deutsches Museum, CT scan data will be produced of both our devices and of a fully functional device of a private collector, in order to finally fully understand the algorithm.

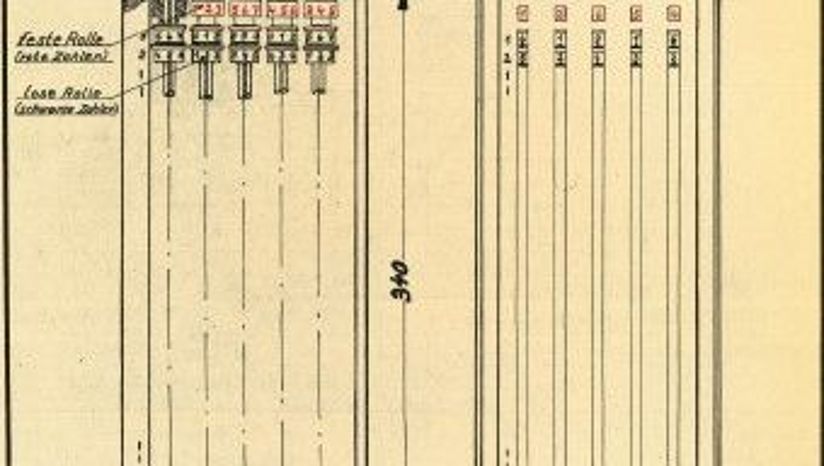

This so-called difference forming device (roller apparatus) simplified a technique of cryptanalysis that was very common in World War II. Photo: Jensen, Willi: Hilfsgeräte der Kryptographie. Diss. Flensburg 1955. Universitätsbibliothek TUM, Garching, Signatur 0109/I 305+306

The auxiliary devices of OKW/Chi

Between 1942 and 1945, the Wehrmacht’s cipher section designed mechanical and electro-mechanical devices to break intercepted encrypted messages. Most probably all equipment was destroyed at the end of the war. Only dredged-up remnants of one type of equipment could be recovered by German divers. In order to learn more about the construction and operation of these cryptanalytic devices, this study is evaluating archival documents.

Link zum Objekt der Sammlung Heusenstamm

Link zur HistoCrypt2020/ Zur Veröffentlichung über die Hilfsgeräte

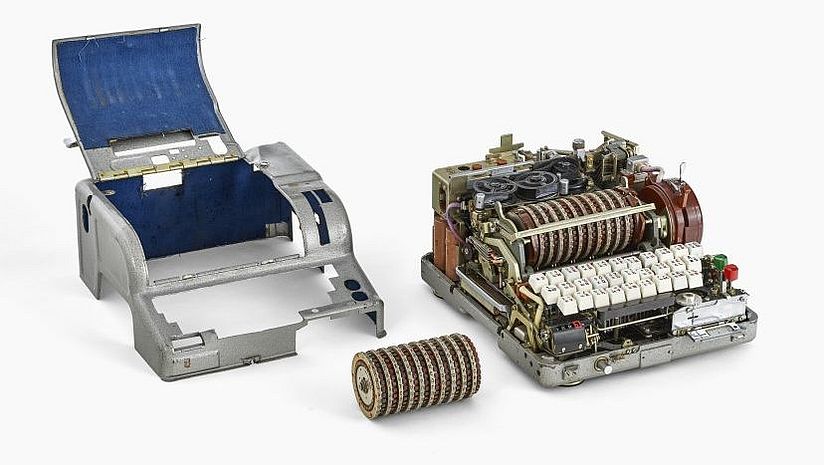

Our model of the Fialka survived the so-called demilitarisation at the end of the Soviet Union, but the input and output rotors have been broken and the housing shows traces of fire damage. Photo: Deutsches Museum, Konrad Rainer | Konrad Rainer

Conservation of a Czech Fialka M-125 (USSR)

Our example of a rare cipher machine called Fialka, which was acquired in 2018, was thoroughly examined and restored in our conservation workshop for scientific instruments. The result: a previous owner had demonstrably assembled a Czech variant from several fragments that at first glance appeared to be coherent.

However, the keyboard was assembled from several models and partially repainted, the metal bonnet adapted accordingly. For the exhibition Image Script Codes, a CAD keyboard set matching the construction type is drawn and printed out by the model building workshop using 3D printing. This way, our visitors can experience a truly type-typical overall picture of the existing Fialka technology as soon as the exhibition will open.

Alexis Køhl sent his invention to the Deutsches Museum in 1918, inquiring as to “whether it would please the esteemed director to accept my gift of a cipher writing apparatus (…) that I designed.” Photo: Deutsches Museum, Konrad Rainer | Konrad Rainer

The Automatic Cryptograph by Alexis Køhl (1846-1920)

In 2013, a chance depository find turned out to be the oldest encryption machine of the Deutsches Museum. The so-called Kryptograf by the Danish engineer Alexis Køhl was sent to the Deutsches Museum from Copenhagen in 1918 by the inventor himself with the announcement that he himself would soon be travelling to Munich to talk about his device. Unfortunately, this trip could never take place, because Køhl fell ill and died shortly afterwards.

Dating of the machine

Thus this machine remained imprecisely documented and was estimated by the curator at the time to be constructed in 1876 – a date that did not seem to be consistent. Meanwhile, research conducted in Denmark by various institutions, archives and experts revealed that our cryptograph was probably made around 1890 at Professor E. Jünger’s “Mechanical Etablissement” in Copenhagen, a highly respected company with which Köhl had a good working relationship.

![[Translate to English:]](/assets/_processed_/f/d/csm_Bild-1_Ephmeride-des-Kleinen-Planeten-Hecuba_824f1969c4.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/assets/_processed_/f/1/csm_Forschungsinstitut_Projekt_Algorithmische_Wissenskulturen_Header_HashagenSeising_743a1da746.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/assets/_processed_/9/4/csm_Forschungsinstitut_Projekt_Zuse_Headerbild_CD_57903_5bb36f91cf.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/assets/_processed_/0/6/csm_Logo_for_memory_RGB_600_a81aebaffa.jpg)